Christie Nicoson

There is a notable gender imbalance in climate decision-making, with only around 20% of countries sending women to the United Nations climate negotiations,[1] and court decisions have down-played that people of different genders experience harm from climate change differently. Recently, a group of 2,000 Swiss women brought a ‘landmark’ case seeking to hold their government responsible for failing to addressing climate change; the European Court of Human Rights decided in April 2024 that their ‘victimhood’ status was disconnected from their characteristics as elderly women.[2]

These gaps point to a worrying trend. Despite increasing policy papers, academic analysis, and grassroots calls emphasising specific gender impacts of climate change – for instance, alerting that women are often more vulnerable to negative impacts of climate change[3] – policies and legislation on climate change largely still overlook gender issues.

If we look beyond questions of ‘who and how’ in courts and policymaking, what does it mean to say that climate change is a gender issue?

As a political scientist, I study the dynamics of how different people experience climate change. While researching this, I realized that how we know what ‘climate change’ is in the first place is deeply gendered.[4]

Climate change is a gender issue – look to the science

Feminist researchers have long taught us that knowledge is deeply situated. All knowledge comes from somewhere, and that the way in which it is used also has a history and context. Most people learn what climate change is based on international research – reports produced by scientists that tell us how much and how fast the earth’s temperature is raising, changes in soil and water, or predicting amounts of sea level rise.[5] How do we know about these changes? Climate science relies on scenarios and trend detection that makes it possible to see change over long periods of time and great scales.

The tools used to measure and observe climate change rely on technologies developed through military and economic power underlying capitalist patriarchal modes of production.[6] That is, climate science has largely developed through ‘neutral’ scientific models and ‘value-free’ abstractions.[7] This stems from a way of viewing the world that separates categories of humanity via race and gender, inextricably linked with coloniality’s Eurocentric patriarchy and capitalism.[8] As Sandra Harding writes, “Gender politics has provided resources for the advancement of science, and science has provided resources for the advancement of masculine domination”.[9]

Why does it matter how we ‘know’?

With this way of knowing as our basis, only certain solutions or responses to climate change appear or even seem possible. Consider the goal to limit global warming to 2°C: certain value judgements are necessary to determine that other types of harm already surpassed by that limit is acceptable.[10]

Risk and harm thresholds or goals for limiting global warming come laden with value judgments that may obscure some groups of people, ecosystems, and nations.[11] Extensive claims of climate change as a threat to ‘future generations’ marginalizes crip and queer lives through explicitly tying visions of the future to the Child.[12]

Where the climate hits home

Certainly, climate change science is not without conscience nor wrong, nor that all climate action is without benefit. However, this starting point prompts consideration of what lies beyond these ways of knowing and doing. These gender issues are more than just a matter of ‘knowing’; they are driving climate change itself.

For instance, higher consumption and production in the Global North generate harmful emissions causing climate change.[13] Colonial nations (as opposed to colonized places) also tend to dominate spheres where policy problems and solutions are imagined and devised.[14] These same countries’ militaries (the US as forefront) are also among the largest consumers of fossil fuels and emitters of greenhouse gases.[15] Some researchers argue that meat-based diets, a major contributor of greenhouse gas emissions,[16] are motivated by and sustained as a symbol of hegemonic masculinity.[17]

These do not point to inherently gendered environmental footprints, but do illustrate the role of gender norms and structures intersecting with race and class that drive climate change.[18]

How we know a problem matters. The next time (no doubt, soon) climate enters policy debates or the court room, we ought not stop ‘counting’ gender in terms of bodies represented, but look to the constructs of knowledge upon which our judgements rest.

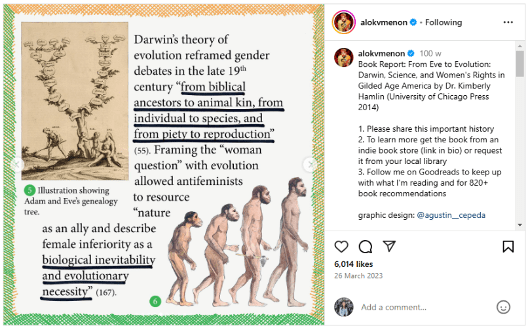

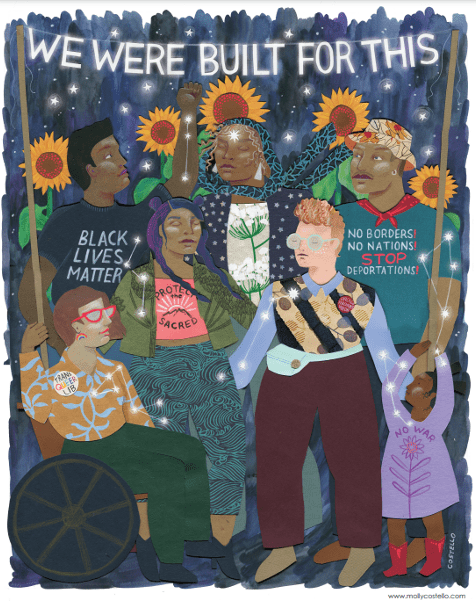

Images:

- ALOK, https://www.instagram.com/p/CqQNDybu_YY/?img_index=5

- How do the impacts of 1.5C of warming compare to 2C of warming? By Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief via http://carbonbrief.org/scientists-compare-climate-change-impacts-at-1-5c-and-2c/

- Built4This by Olly Costello, https://ollycostello.com/art-community

[1] Green, S. (2020). ‘Gender, Climate Change & Participation: Women’s Representation in Climate Change Law and Policy’, CCJHR Working Paper Series 10. https://www.ucc.ie/en/media/academic/law/CCJHRWPSNo10ShannonGreeneGenderClimateChangeParticipationApril2020(1).pdf

[2] Lupin, D. and N. Urzola (2024). KlimaSeniorinnen and Gender. Climate Law blog series on Climate Litigation. https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/climatechange/2024/05/09/klimaseniorinnen-and-gender/

[3] UN Women (2022). ‘How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected.’ https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2022/02/explainer-how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected

[4] Nicoson, C. (2024). Peace in a Changing Climate: Caring and Knowing the Climate-Gender-Peace Nexus. Faculty of Social Science. Malmö, Sweden, Lund University. Doctor of Philosophy: 193. Available at https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/peace-in-a-changing-climate-caring-and-knowing-the-climate-gender

[5] IPCC (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. e. Romero. Geneva, IPCC: 184.

[6] Mies, M. and V. Shiva (2014 [1993]). Ecofeminism. London, Zed Books.

[7] O’Lear, S. (2021). Closing thoughts and opening research pathways on geographies of slow violence. A Research Agenda for Geographies of Slow Violence. S. O’Lear. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing: 225-231.

[8] Lugones, M. (2008). “Colonialidad y género.” Tabula Rasa 9: 73-101.

[9] Harding, S. (1986). The Science Question in Feminism. Ithaca, Cornell University Press. (112)

[10] Seager, J. (2009). “Death by Degrees: Taking a Feminist Hard Look at the 2° Climate Policy.” Kvinder, Køn & Forskning (3-4).

[11] MacGregor, S. (2014). “Only Resist: Feminist Ecological Citizenship and the Post‐politics of Climate Change.” Hypatia 29(3): 617-633.

[12] Hall, K. Q. (2014). “No Failure: Climate Change, Radical Hope, and Queer Crip Feminist Eco-Futures.” Radical Philosophy Review 17(2): 203-225.

[13] Hickel, J. (2020). “Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary.” The Lancet Planetary Health 4(9): e399-e404.

[14] Perry, K. K. and L. Sealey-Huggins (2023). “Racial capitalism and climate justice: White redemptive power and the uneven geographies of eco-imperial crisis.” Geoforum: 103772.

[15] Crawford, N. C. (2019). Summary: Pentagon Fuel Use, Climate Change, and the Costs of War. Providence, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

[16] Watts, N., et al. (2021). “The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises.” The Lancet 397(10269): 129-170.

[17] Rothgerber, H. (2013). “Real men don’t eat (vegetable) quiche: Masculinity and the justification of meat consumption.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 14(4): 363-375.

[18] Daggett, C. (2018). “Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 47(1): 25-44.

Leave a comment