Andrew Jackson

21 November 2025

I. Introduction

A clamour of praise greeted John Collison’s “how to get Ireland moving” Op-Ed following its publication in the Irish Times on 25th October: the Irish Times’ Political Editor described the piece as “considered, informed and pertinent,” and this appears to have reflected the views of a considerable number. The article is said to have “stirred coalition debate”, and Collison has since been invited to address an Oireachtas committee on the issues raised by his piece.

But just how considered and informed was it, and what were its influences?

While Collison’s 2800-word “sermon to the nation”, as Colin Sheridan called it in the Irish Examiner, seemed to emerge fully-formed from nowhere, many of its ideas reflect the work of Progress Ireland, a think tank Collison and his brother Patrick have backed financially (having reportedly “chipped in €1m, or more”). The Sunday Independent’s headline referred to it simply as “Collisons’ new think tank” on its launch in 2024. However, it is also funded by several others, including “Emergent Ventures”, a grant programme administered by Tyler Cowen of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in the US, a “state capacity libertarian” economist who co-authored an Op-Ed with Patrick Collison in 2019 on “a New Science of Progress”.

Progress Ireland’s pitch to prospective funders (kudos Lois Kapila in the Dublin Inquirer) sets out its stall clearly: “[T]he Irish [think tank] scene is wide open, with no real competitors,” we are told. “Ireland is highly conformist and is more prone to deference to elite or expert consensus than our British counterparts”. Bit rude, but go on.

“[T]here are few organised voices for growth, abundance, and optimism in the political landscape [in Ireland]”, “We believe growth goes a long way to solving most public policy problems”. OK, growth, abundance, got it. Small ‘a’ abundance is “our North Star”, according to Progress Ireland’s Executive Director.

Capital ‘A’ “Abundance” is a “much-talked-about” book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson which has featured prominently in US policy discourse over the past year. Reviewing the book in March, the University of Michigan’s Noah Kazis wrote, “Klein and Thompson’s story of sclerosis is of a ‘system so consumed trying to balance its manifold interests that it can no longer perceive what is in the public’s interest.’ Opposing the political scrum, they instead valorise ‘strong leadership’. Any countervailing power is suspect. For various abundance thinkers, this has included legislatures and courts, environmentalists, unions and neighbourhood associations. Notably, their scepticism of non-majoritarian influence extends less frequently to corporate power.”

Collison’s brother Patrick is also a fan of Abundance, an agenda which “embraces YIMBYism [Yes in My Backyard] and regulatory rollbacks, seeking to accelerate development and address bottlenecks to progress,” according to Julia Black in The Information. As well as being a fan, Patrick Collison is also an inspiration for Abundance’s authors, with the authors “openly [citing] him as a major wellspring of inspiration.”

Along with holding an annual camp summit, writes Black, “[Patrick] Collison has set up a series of organizations to form a bedrock for the spread of his philosophy, which is broadly called progress studies. Collison’s efforts exist within a broader, interconnected network of Silicon Valley elite, lawmakers, think tanks and political operatives who all want some version of an America [read: Ireland] that embraces a pro-growth, pro-tech, anti-regulation stance: It’s the abundance-verse, a network of organizations that cross-pollinate and collaborate extensively.”

Anyway, back to Progress Ireland’s pitch: “Ireland is a small place – politicians are relatively accessible, and there are few other orgs like ours competing for their attention”; “We will align and curate our pitches to present win-win proposals to politicians. […] We will produce work that advances their goals”; “We will pressure politicians via the media. Sometimes this will be at their request”; “Officials can’t enact ideas but they can slowly kill them”; “We will socially de-risk ourselves with officials by appearing as friendly faces at department conferences, policy launches, and speaker events”. “How will you avoid getting pigeonholed as right wing tech bros?” they ask. “Branding” is the first answer (though in fairness they also include “Policy choices” and “Funders” in their list). Et cetera.

Clearly influenced by Progress Ireland’s work, as well as by the books “Why Nothing Works” by Marc Dunkelman (which is cited in Collison’s Op-Ed) and “Abundance” (which is not; reviewed together here), the proximate trigger for John Collison’s piece seems to have arisen two weeks prior to its publication, at the official opening of Stripe’s new Dublin HQ on 9th October.

There, the Taoiseach told the gathered attendees, including Collison, that “What is killing us [in Ireland] is delivery, planning and judicial review. We do need to have a real debate about the public good versus what I might term the excessive assertion of individual rights,” he added. These will be familiar themes to anyone who has been following the public debate in Ireland over the past months.

Collison seemed to warm to these remarks, “mooting that the existing policies in the planning system have an ‘implied value system that I am not sure the Irish people would choose’.” He would return to this theme prominently in his Op-Ed.

In his piece, Collison seeks to build a case for planning and broader governance reform by analysing (or at least mentioning) specific projects, before concluding “Let’s analyse not just specific projects but the broader system and how it delivers for us.”

However, since his discussion of specific projects forms an important building block in his argument, it’s worthy of close attention. So let’s consider some of the examples Collison cites, alongside the principles he says they evidence.

II. “Agencies have values and goals of their own”

Seeking to establish that “it’s a bad idea to leave the running of the country to agencies and officials”, and under the banner that “agencies have values and goals of their own, and these values are sometimes out of step with the rest of the country,” Collison cites a series of examples, before concluding “Who signed up for this?”

This rhetorical device lends itself to egocentric bias: I don’t agree with a particular decision and my views seem to reflect the values of broader society, and this asserted consensus is being thwarted by agencies with their own goals and values which don’t reflect ours.

Depopulation

In this vein, Collision claims that “The Department of Housing has decided to intentionally depopulate the east of the country.” Really? This is totally unsupported by evidence or argument in the piece.

Census 2022 “shows that the population of Dublin grew by 8% to 1,458,154, which means the number of people in the county rose by 110,795 between April 2016 and April 2022. Over the same period, Ireland’s population grew by 8% from 4,761,865 to 5,149,139.” Ireland’s population then rose each year from 2022 to 2025 (see CSO statistics here). At the end of April 2025, Ireland’s population was estimated at 5,458,600 (up from 5,149,139 in April 2022). “Looking at where people reside,” says the CSO, “the proportion of the population living in Dublin has risen from 28.2% of the total in 2019 to 28.7% of the total in 2025 and now stands at 1,568,000 people [up from 1,458,154 in 2022].”

The revised National Planning Framework of April 2025 envisages the population of the Eastern and Midland region growing by 470,000 between 2022 and 2040; within that, the population of Dublin city and suburbs is targeted for growth of +295,000 people.

Collison’s “depopulation” claim might have been intended as hyperbole in the context of the housing crisis, but was it considered and informed commentary?

Lesser Horseshoe Bats in Killarney

Under the same “agencies have their own values and goals” banner, Collison cites the following example from the field of nature conservation: “Two hundred and twenty eight homes were blocked in Killarney because they would interrupt the commute of a roost of horseshoe bats. Who signed up for this?” he asks.

The first and most important answer to this is simply: these homes were not blocked. To claim that they were is highly misleading. In August 2022, An Bord Pleanála (ABP, as it was then) refused permission to the developer, Portal Asset Holdings Limited. The application was made directly to ABP because this was under the (now defunct) Strategic Housing Development (SHD) system, which was intended to speed up housing delivery by cutting out the local authority stage of planning permission.

Informed by the evidence and arguments set out in its inspector’s 109-page report, ABP concluded that it was legally precluded from granting permission because the documentation submitted by the applicant “did not provide sufficient scientific reasoning to clearly eliminate the likelihood of significant adverse effects” on Lesser Horseshoe Bats and on Killarney National Park Special Area of Conservation (SAC), an EU protected area.

However, this was not the end of the story. The developer subsequently reapplied for permission – now under the successor scheme to SHD – and this time, in November 2024, it obtained permission from ABP, having made some changes to its scheme (now 224 homes), revised its documentation, consulted with the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and committed to various mitigation measures relating to potential impacts on Lesser Horseshoe Bats and the National Park. As such, ABP was able to conclude that the project would not adversely affect the integrity of Killarney National Park SAC.

Rather than building the homes, however, in July 2025 the developer, Portal Asset Holdings, was looking to flip the land – now with planning permission for 224 homes – for €9.5 million.

Suggesting that 228 homes were “blocked” in Killarney because of bats, without mentioning the highly relevant and more recent context that the developer later received permission at the site and has since been trying to sell the land (now with planning for 224 homes), is remarkable.

The second answer to “Who signed up for this?” is that our elected representatives signed up for this, by way of the EU Habitats Directive, which exists to protect Europe’s most threatened and endangered species and habitats, and which was negotiated in painstaking detail by Ireland and its fellow EU Member States over the course of four years.

The conservation status of the Lesser Horseshoe Bat (Crú-ialtóg bheag) in Ireland was assessed as “Unfavourable-Inadequate and declining” in the most recent national assessment, owing to concerns about habitat loss and landscape connectivity. It is confined to six west coast counties (Mayo, Galway, Clare, Limerick, Cork and Kerry), and the Irish population is considered to be of international importance.

Credit: Frank Greenaway

Far from representing values that are “out of step”, the Habitats Directive is in fact very popular. A proposal from the European Commission president to renegotiate the directive about a decade ago was rejected after it provoked the largest ever public response to an EU consultation, with more than 500,000 responses demanding (successfully) that the directive be preserved.

Again, ABP’s decision to refuse permission in 2022 and subsequently to grant permission in 2024 did not somehow reflect ABP’s (apparently changeable!) values and goals. Rather, the 2022 decision vindicated the rule of law, in the form of the Habitats Directive. The 2024 decision to grant permission came after the developer took steps to ensure that the project would not adversely affect protected species and habitats. This is not an example of system failure – it’s an example of the system operating exactly as it should.

Neither ABP nor the bats can be blamed for the fact that the developer hasn’t delivered on the grant of planning permission in Killarney, just as they can’t be blamed for the estimated 90,000 other homes nationally (including c.45,000 in Dublin) which reportedly had unused planning permissions in 2025.

Dublin airport

Also under the banner “agencies have their own values and goals”, Collison claims that “An Coimisiún Pleanála [ACP] has blocked the demolition of old concrete ramps at Dublin Airport.”

We are now in the field of architectural heritage. While it’s true that ACP refused permission for demolition of (the pejoratively-described) “old concrete ramps”, it’s worth noting that demolition was first refused by Fingal County Council in February 2025, before being refused by ACP on appeal. So two planning authorities considered the evidence and arguments in detail and both reached the same conclusion.

The ramps are not just any “old concrete ramps”, as Collison might have readers believe. They will be instantly recognisable to anyone who knows Dublin airport.

Credit: images from Angela Rolfe’s submission to Fingal County Council

In her submission to Fingal County Council, Angela Rolfe – president of ICOMOS (the International Council on Monuments and Sites) Ireland – described the ramps as “iconic”, continuing that “the spiral ramps are a very fine and rare example of brutalist architecture in Ireland.”

Noting that Dublin Airport Authority’s (DAA) planning application “does not state what is proposed for the development site that will be created after the demolition of the spirals”, Rolfe concludes that “Demolition of these fine examples of mid 20th century structural engineering, beautifully executed by the contractor, would not only destroy a unique example of Irish Brutalism but it would lead to the totally unnecessary release of embodied CO2.”

In its decision on appeal, having considered the evidence and arguments at length by way of its inspector’s 59-page report, ACP concluded that “the spiral ramps are part of the architectural heritage of Dublin Airport… [they] are of technical and architectural merit by virtue of their brutalist design, associated concrete construction and their unique architectural form and shape which reflect a distinctive feature adjacent to the Terminal 1 building.”

ACP also found that demolishing the ramps would “expose the crude architectural detailing of the existing structures to the rear of the spirals, including the prominent vertical infrastructure elements of the energy centre currently screened by the spiral car park ramps and, as such, would erode the character of the area”.

“Therefore,” said ACP, “in the absence of evidence and appropriate rationale or justification,” the proposed demolition of the spiral ramps would be contrary to various provisions of Fingal County’s Development Plan 2023-2029.

Why does John Collison think DAA should be permitted to demolish the spiral ramps? Simply because they want to? As a co-owner of Dublin’s Weston airport and a self-confessed “aviation fanatic”, Collison may perhaps feel an affinity with fellow airport owners – who knows? However, we have no idea why he supports demolition of the ramps, because he gives no indication in his Op-Ed.

Far from representing ACP’s “own goals or values”, a county’s development plan is made by the elected councillors of the relevant local authority, in this case Fingal County Council. The Supreme Court has thus described an adopted development plan as “an environmental contract between the planning authority, the Council, and the community, embodying a promise by the Council that it will regulate private development in a manner consistent with the objectives stated in the plan” (The Attorney General (McGarry) v. Sligo County Council [1991] 1 IR 99).

Readers may think Collison has pulled the rabbit from the hat here with his claim that in development plans “you will not find specific rules. Instead you’ll find a soup of dozens of goals and targets. Like Mass before Vatican II, interpretation of these texts is the domain of individual planning officers.”

However, even if a planning decision at the local authority level (which is typically informed by a range of internal reports and external submissions, from a range of individuals) is ultimately taken by an individual, the conclusion that a proposed development would materially contravene a development plan is not necessarily the end. Such a development can still proceed if the correct procedure is followed, involving a vote of the elected councillors: not an individual planning officer.

Further, the minimum quorum for decisions by ACP on appeal is three: so the interpretation of a development plan by ACP is not down to an individual planning officer. Equally, ACP can similarly permit a project in material contravention of a development plan in certain defined circumstances.

In the case of Dublin airport’s spiral ramps, planning permission was unanimously refused on appeal by a 3-person quorum of ACP. So three individual Commission members, having considered the evidence and arguments put before them, considered that permitting the demolition of Dublin airport’s spiral ramps, without an appropriate rationale or justification, would contravene Fingal County’s Development Plan, which represents a “contract” between the Council and the public it serves.

John Collison might not like this decision (though again, he doesn’t indicate why), but that doesn’t make the decision wrong. It doesn’t mean the decision is out of step with the values of the rest of the country. And it certainly doesn’t mean that the decision reflects ACP’s goals and values.

Johnny Ronan’s Dublin towers

“Some agencies’ decisions don’t even further their own stated goals,” claims Collison. “In August,” he continues, “An Coimisiún Pleanála ruled that the old Citibank building on the Liffey’s North Quays couldn’t be knocked down and redeveloped. Their reason: the construction of a new building would result in the emission of carbon. So instead, new development will happen on green fields, far from existing transport links and city cores, and result in more commuting and more carbon emissions.”

About this “old Citibank building”: it’s “barely 25 years old and in good condition and does not show signs of deterioration or disrepair,” according to the planner’s report for Dublin City Council.

Planning permission was sought by NWQ Devco Limited (a Johnny Ronan company) for the demolition of the existing building and basement and redevelopment to provide “an office led, mixed use development in a building ranging in height from nine to 17 storeys over lower ground floor level and two levels of basement. The building would be formed of four blocks comprising Block A (17 storeys), Block B (12 storeys), Block C (10 storeys) and Block D (nine storeys),” significantly exceeding the prevailing heights at the proposed development location.

According to ACP’s inspector’s report, “The development would incorporate retail/café/restaurant use at ground floor level. Three internal arts/cultural/community spaces would be provided, one at lower ground floor, one at first floor level and a viewing deck on level 16. A further external space would be provided in the form of a new landscaped park to the east of the site, providing a new pedestrian link from North Wall Quay to Clarion Quay. All remaining internal spaces would be in office use.”

Dublin City Council refused permission in April 2024 for a host of reasons, including contravention of the Dublin City Development Plan 2022-2028, including the fact that the Plan “seeks to promote and support the retrofitting and reuse of existing buildings rather than their demolition and reconstruction. The proposed development would set an undesirable precedent for wholescale demolition on similar sites across the city and would therefore be contrary to the proper planning and sustainable development of the area.”

ACP subsequently refused permission too, in August 2025. This from ACP’s Order: “Having regard to the prominent and sensitive location of the subject site which fronts onto the River Liffey and is within the Liffey Quays Conservation Area, in close proximity to neighbouring residential properties, and on a site that is not designated as being suitable for a landmark/taller building, it is considered that the proposed development, by virtue of its excessive height, bulk, massing and form, would constitute an overly dominant and isolated tall building that would be at odds with the surrounding context and would seriously injure the visual amenity of the Liffey Quays and key views along the river corridor.” The proposal would thus contravene Dublin City’s Development Plan, found ACP.

So climate change considerations were not the only reason for refusal. However, “Having regard to the age, form, and condition of the existing office building and the results of the Whole Life Carbon assessment, [ACP] considered that the wholescale demolition of the existing building would be both premature and unjustified and would set an unwelcome precedent for demolition on similar sites in Dublin.”

That is, based on the evidence before ACP, demolishing an existing building ahead of its expected lifespan rather than refurbishing and extending the building, would generate significantly greater carbon emissions, during what the Oireachtas has itself declared the climate emergency. Either option would of course generate emissions – that’s the nature of building – but knocking a 25-year-old building, excavating a massive basement, and building something entirely new is much worse.

Collison claims that “new development will [now] happen on green fields, far from existing transport links and city cores, and result in more commuting and more carbon emissions,” but again he offers no evidence for this.

Has planning permission since been sought by the developer for four (or any) office blocks – ranging from 9 to 17 storeys – on a greenfield site? Why can’t a developer refurbish and extend the 25-year old Citibank building (or develop somewhere else in the city core) rather than seeking to demolish what is a still a relatively new building, which would worsen climate change and impose further costs (including contributing to what the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council and the Climate Change Advisory Council have jointly described as “colossal” financial costs) on current and future generations? Should we just let developers do whatever they want?

III. “Agencies can’t make trade-offs”

Having thus failed to make out his case on the grounds of “values and goals”, Collison moves on to allege that “The third problem with government-by-agency is that the agencies can’t make trade-offs. If the pursuit of their goal blocks something else important – well, that’s not within their remit.”

His examples come quick-fire:

“we have the state-funded An Taisce blocking the Galway ring road, the M3 motorway and the Shannon LNG scheme”

An Taisce is an environmental NGO: non-governmental being the key word. It’s not a government agency and it’s not involved in running the country in any sense, so it’s hard to see how Collison can use it as an example of why “it’s a bad idea to leave the running of the country to agencies and officials,” as he puts it. Yes, An Taisce receives some core funding from the State for its advocacy work (and separate funding for its education work), but so do many NGOs in Ireland: all of whom remain NGOs, all in receipt of some State funding, none of whom are required to toe the line, of course.

Collison seems to think that the Galway ring road and the Shannon LNG scheme should not be blocked, presumably on the basis that “trade-offs” should count in their favour, but he offers no argument or analysis in support of this. An Taisce did not judicially review either of these projects in any event, though it certainly engaged in the planning process relating to them, not least on the grounds of climate change. However, climate change goes unmentioned in Collison’s Op-Ed, such that the “trade-offs” imposed on current and future generations by climate-harming projects go totally unanalysed.

Collison’s third example, the M3 motorway, a toll-road which passes through the Tara Valley, skirting the Hills of Tara and Skryne, was “one of the most controversial road schemes ever built” in Ireland, according to RTÉ, and opened for business in 2010, so it’s an interesting use of the present participle in “we have […] An Taisce blocking”.

We know what John Collison thinks about the M3, but did you know that in 1902 W.B. Yeats described Tara as “probably the most consecrated spot in Ireland”? George Eoghan, a Professor of Archaeology at UCD who was present during the first archaeological excavations at Tara in the 1950s, called the construction of the M3 motorway “one of the greatest shameful acts of cultural vandalism that took place in any part of Europe”. Independent RedC polls conducted in 2005 and 2008 showed that 55% and 62% of those surveyed thought the motorway should not go through the Tara Valley.

In these circumstances, does Collison seriously think that An Taisce – an NGO which is literally the National Trust for Ireland – should not have done its best to prevent the motorway’s impacts on cultural heritage and the environment, including by way of judicial review (in respect of which An Taisce was in fact refused leave, such that its case did not go ahead)? Arising from the M3 dispute, Ireland was ultimately found to have mistransposed EU law by excluding demolition works from the scope of environmental impact assessment, in Case C-50/09 – a case taken against the State by the European Commission.

Bhreathnach, Fenwick and Newman argued in 2004 that “The issues raised by this case transcend the question of Tara v. the M3 and touch on the value that we as a nation place on our cultural heritage and its role in contemporary society. In today’s Ireland, it seems, heritage is at best a brand-identity and at worst an obstacle to the generation of wealth among developers.”

Similar arguments have been made regarding the Roadstone quarry which has eaten away the (now at best Half) Hill of Allen in Co Kildare, the ancient seat of Fionn mac Cumhaill. Do “trade-offs” make this acceptable? Should environmental and heritage NGOs stay silent?

“We have officials at Fingal County Council throttling flights out of Dublin Airport”

Presumably Collison is here referring to planning conditions that attach to developments at Terminals 1 and 2 at Dublin Airport, which provide that the combined capacity of the terminals shall not exceed 32m passengers per annum unless otherwise authorised by a further grant of planning permission. These conditions were attached by An Bord Pleanála (as it was then) in 2007 and 2008, not Fingal County Council.

The Irish Aviation Authority (not Fingal County Council or ABP) then imposed a seasonal Passenger Air Traffic Movement (“PATM”) cap in 2024, reflecting the planning conditions imposed by ABP. DAA and various airlines challenged this before the High Court – pesky judicial review! – and the High Court placed a stay on the cap until the determination of the proceedings.

As the High Court put it, “The effect of the stay on the PATM seat cap is that the number of passengers using the Terminals in the calendar year 2025 is forecast to exceed 32mppa.”

Indeed, the Irish Times reported on 4th November that “DAA chief executive Kenny Jacobs has said he expects the 32 million annual passenger cap at Dublin Airport to be breached ‘early next week’ [i.e. last week] amid strong demand for travel,” with seven weeks of the year still remaining. DAA boasted recently of a “record-busting October”, noting that “October [2025] was the seventh consecutive month of passenger growth, continuing a trend that started in April when the High Court imposed [its] stay.” Meanwhile, records were also being bust in other spheres, with October 2025 representing the third-hottest October on record globally.

This will be the second successive year the 32m cap has been breached, since 33.3m passengers passed through the airport’s terminals in 2024. DAA forecasts more than 36m passengers in 2025.

DAA applied in December 2023 to raise the passenger cap to 40m passengers as part of a wider multi-billion euro infrastructure plan (this remains under consideration following the submission by DAA of significant further information in November 2024), and separately applied to raise the cap to 36m in a standalone application lodged in December 2024. This latter application was deemed invalid by Fingal County Council in January 2025 owing to non-compliance with the Planning Regulations. DAA has since reapplied.

Having received complaints from members of the public in 2023 and 2024, and in keeping with its legal obligations under section 154 of the Planning Act 2000, Fingal County Council issued a planning enforcement notice to DAA in June 2025 relating to breach of the passenger cap.

I say “obligations” because where, following an investigation under section 154, a council establishes that unauthorised development has been or is being carried out and the developer in question has not proceeded to remedy the position, then the authority must issue an enforcement notice, unless there are compelling reasons for not doing so. As Fingal County Council explained, “the information submitted by [Dublin airport] does not constitute sufficient grounds to prevent further action. The investigation has determined that a breach of the relevant planning conditions has occurred and remains ongoing.”

So the Council was in effect legally required to issue an enforcement notice, but the Council then bent over backwards to facilitate the airport, giving DAA two years to comply with the passenger capacity conditions, so as to allow DAA to “progress their planning applications to increase passenger capacity at Dublin Airport or take such other steps as they consider appropriate to achieve compliance.”

So Collison claims Fingal County Council is “throttling flights out of Dublin airport,” while the airport is not in fact operating under the 32m passenger cap at all, while DAA boasts of “record-busting passenger numbers” (expected to exceed 36m in 2025), while Fingal County Council has given the airport until 2027 to achieve compliance, and while the Government is in the meantime reportedly working on legislation to scrap the cap altogether.

Go figure, as an American tourist might have muttered whilst pushing through the crowds in Terminal 2 last week, unknowingly becoming the 32 million and somethingth passenger this year.

“Inland Fisheries Ireland blocks flood remediation works”

It’s hard to know where to start with this one – mainly because Collison provides no further information. He might be referring to Inland Fisheries Ireland’s (IFI) intervention in the Bandon river case in Co. Cork (this is what Google seems to think), but who knows?

The “controversial” €16m flood defence project in Bandon resulted in an outcry at the time. Particular concerns were raised when the riverbed was effectively turned into a road for “large earth-moving diggers and trucks” in October 2018 (see photos). This despite the scheme’s own planning documents promising that such instream works would take place only between May and September, as outlined in IFI Guidelines regarding permission for instream works, to minimise the impact on salmon (thus avoiding the main periods of migration and spawning for this protected species).

Credit: Peter Powell-Berz. All photos were taken in October 2018, when no instream works were supposed to be taking place. The photos do not show the incident that later resulted in a successful prosecution by IFI, described further below.

Inland Fisheries Ireland said it was “gravely concerned”, but it didn’t block the works. It did successfully prosecute a contractor for the OPW in relation to a fish kill caused by the project in 2017, who was ultimately fined €10,000.

Summing up, Judge Mary Dorgan said it was “absolutely incumbent on the OPW to remember that they are acting for the people of Ireland and it’s their obligation to protect nature” while also keeping the public fully informed about the extent of the works. The Judge added that it shouldn’t be a case of saying “we have the money, we do the work, we dig up the river, we put a road down the middle of it and it will all be grand.”

“The Heritage Council is blocking the demolition of a wall for the N2 bypass”

Again, it’s unclear what Collison is referring to here. ACP granted permission for the N2 Slane bypass in June 2025. The location is of course sensitive given the bypass’s proximity to the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site. The Heritage Council expressed concerns about the proposed demolition of sections of rubble stone walls, themselves protected structures. However, ACP granted permission for the works, subject to implementation of all mitigation measures in the Environmental Impact Assessment Report.

While a former Attorney General has reportedly brought an action for judicial review against the permission for the bypass, how (if at all) the Heritage Council is blocking “the demolition of a wall” is unclear, and Collison does not elaborate.

IV. “Environmental goals have created stasis”

Collison’s litany of planning examples builds to his concluding message: “We should notice that environmental goals have created stasis, planning has turned into the tyranny of the minority veto, and proactive city design has simply ceased. Process has been allowed to take precedence over outcomes.”

Really? Have environmental goals really created stasis in Ireland? Do we really have a system in which the minority veto holds sway?

To focus on the broader context for a moment, far from environmental goals creating stasis, since the 1950s we have been living through what has been termed “The Great Acceleration”, as the Planetary Health Check (PHC) Report 2025 makes clear: “For over 10,000 years, humanity has thrived within a period of climatic stability and a resilient Earth system. This epoch is called the Holocene, and it provided conditions that enabled the rise of agriculture, urbanization, and complex civilizations. However, since the mid-20th century, we have entered a new epoch marked by what is called ‘The Great Acceleration’, where both socio-economic activity and environmental impact have surged exponentially […]. This was the beginning of the Anthropocene – the current era, in which human activity has become the dominant force shaping the Earth system.”

Source: Future Earth (2015)

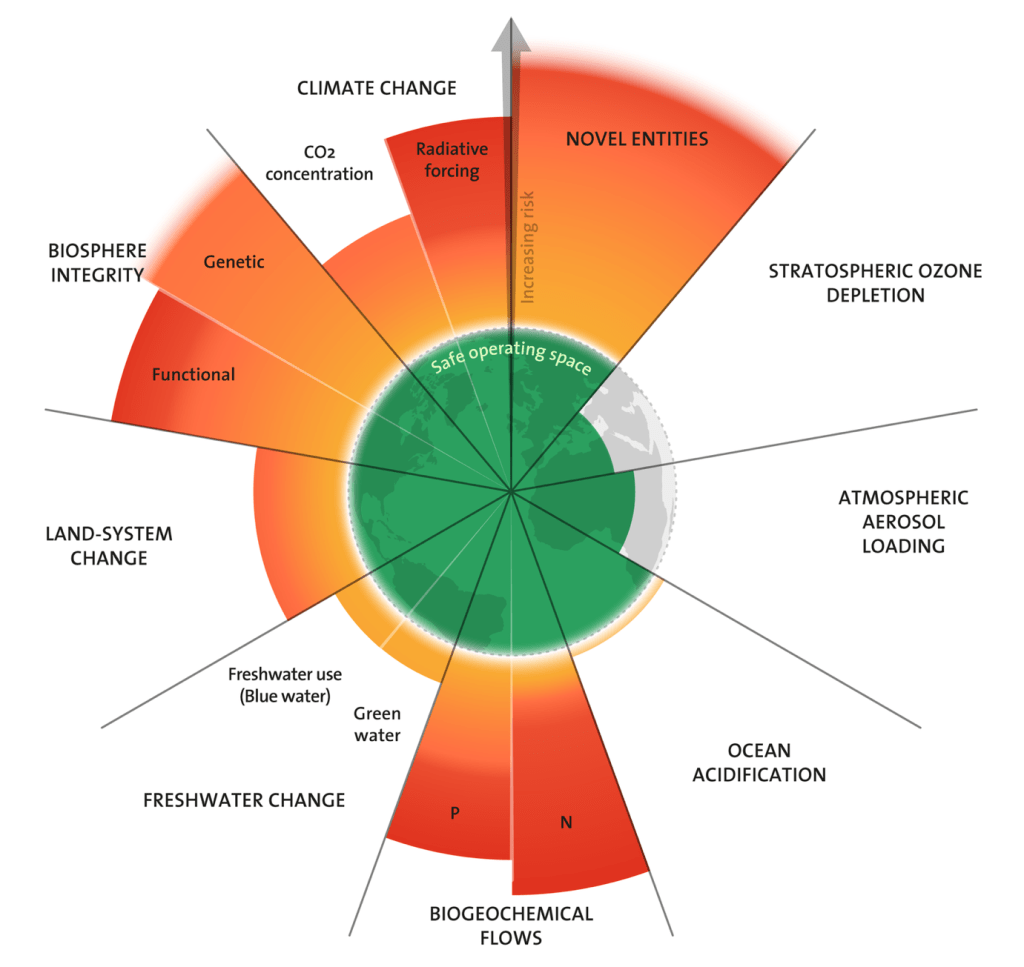

The 2025 PHC report concludes that seven out of the nine “Planetary Boundaries” – the “nine processes that are known to regulate the stability, resilience (ability to absorb disruptions) and life-support functions of our planet” – have been breached, “with all of those seven showing trends of increasing pressure, suggesting further deterioration and destabilization of planetary health in the near future.”

The 2025 update to the Planetary Boundaries. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Credit: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Sakschewski and Caesar et al. 2025.

Consider the following, by way of example:

- Over the past 50 years – during many of our lifetimes – the size of monitored wildlife populations has reduced (based on 34,836 monitored populations of 5,495 vertebrate species), on average, by 73% globally (and by 35% in Europe and Central Asia).

- “Biodiversity is declining across terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems in Europe due to persistent pressures [including] changes in land and sea use, the over-exploitation of natural resources, pollution and invasive alien species, as well as the increasingly severe impacts of climate change” and “the deterioration in the state of Europe’s biodiversity and ecosystems is expected to continue”, according to the European Environment Agency (EEA) in 2025.

- The overall current assessment for nature in Ireland is ‘very poor’ (the same as in 2020), according to the EPA in 2024. “Deteriorating trends dominate, especially for protected habitats and bird populations, and Ireland is not on track to achieve policy objectives for nature.”

- Entire ecosystems are vanishing: e.g. coral reefs will decline by 70-90% globally with global warming of 1.5°C (a threshold we are about to cross), whereas “virtually all (>99%)” will be lost with +2ºC, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Last month, 160 scientists from institutions in 23 countries warned that we have already crossed the thermal “tipping point” for warm water coral reefs.

- These impacts will rebound on “hundreds of millions” in vulnerable communities, since those “who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected”, according to the IPCC.

- Environmental goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through “transformative changes,” according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the EEA (defined by IPBES as “A fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values”).

- “There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all (very high confidence),” according to the IPCC in 2023.

- Global heating of about +7 °C would call the habitability of some regions into question, in the sense that dissipation of metabolic heat would become impossible, inevitably inducing hyperthermia and death in humans and other mammals. Essentially, these areas would become physiologically uninhabitable by humans and other mammals as a result of climate change – we could not survive on the surface of the Earth in such places. Further, “With 11–12 °C warming, such regions would spread to encompass the majority of the human population as currently distributed.” While we are currently some distance from +7°C or +11–12°C, the concept of the carbon budget should nevertheless make it clear (see the IPCC’s SPM.10 on p.18) that so long as we continue adding to the cumulative total of carbon in the atmosphere, we will inevitably trigger associated temperature increases, such that eventual warming of, say, +12°C is perfectly possible with a business as usual approach.

Who signed up for this?

To blame “environmental goals” for creating “stasis” in these circumstances is, frankly, to enter a topsy turvy world in which 2+2=5. If environmental goals have created stasis, they are doing a very good job of hiding the fact, while the environment itself continues to deteriorate at pace.

Collison’s manifesto is not apparently aimed at “getting Ireland moving” to address the Triple Planetary Crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution – issues which are already coming home to roost in our lifetimes and which will haunt our children’s. On its own terms, it’s a manifesto for fossil fuel plants, motorways, bulldozing architectural heritage, lifting passenger caps at airports, knocking 25-year-old office blocks rather than refurbishing and extending them, pitting development against protected species, etc.

The attitude seems to be that whenever environmental issues are in play, “trade-offs” should mean that the environmental goal should give way. However, given the nature and scale of the crises we face, environmental goals surely should function as an emergency brake on business as usual, but this is not the case at present.

As Judge Humphreys noted in the recent Coolglass judgment, “an immediate end to business as usual is a precondition for planetary survival. […] The problem is that the problem [of climate change] is so big that to even describe it factually sounds like scaremongering.”

V. Environmental democracy

Governments are currently under intense pressure to deliver housing and strategic infrastructure and to do so as rapidly as possible at scale. This has in turn brought intense pressure to bear on the rights to participate and challenge decisions in environmental matters.

Clearly, any persistent failure in meeting people’s basic needs must be addressed, presenting as it does threats in terms of social stability and ultimately democracy. Equally, there are clearly threats to social stability and democracy posed by environmental degradation and climate change which, unless urgently addressed, will descend inexorably into what Orla Kelleher and I have described as an “all-consuming crisis without end”.

Commentary in this field, such as Collison’s prominent Op-Ed – blaming “environmental goals” for “stasis” – therefore ought to be “considered and informed”; should be carefully fact-checked before publication; and shouldn’t breeze by without close scrutiny. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts, as the famous saying goes. It’s only fair to those who worked on the various matters that are mischaracterised in Collison’s piece to do full justice to their work.

Hot on the heels of the major planning reforms introduced by the Planning Act 2024 (many of whose provisions have yet to be commenced), Collison’s intervention has merged with a chorus of voices calling for additional restrictions on access to environmental justice, in the form of judicial review. Here, again, the facts and figures deserve closer scrutiny (e.g. Attracta Uí Bhroin here; and data here) than they appear to have received in the public debate up to this point. Did you know, for example, that “members of the public are on track to take 40% fewer [planning/environmental judicial reviews] in 2025 compared to 2024, whereas economic actors (i.e. landowners and developers) are set to increase their [judicial review] activity” and “This year only 1,000 granted [housing] units were judicially reviewed, a decrease by a factor of three since last year,” as Fred Logue writes, based on data compiled by his firm.

There are of course powerful guardrails affecting what can be done in this area, in form of the Aarhus Convention and related instruments of EU law, which require the provision of wide access to justice and access to justice that is not prohibitively expensive. Seeking to further restrict judicial review may result in “satellite litigation” and further delays as a result, as Orla Kelleher has argued.

The influential role of environmental litigation on governance is clear in Ireland. For example, the Supreme Court’s judgment in Climate Case Ireland – a case taken by the NGO Friends of the Irish Environment – was described as a “turning-point for climate governance in Ireland” by Áine Ryall. In 2021, significant amendments were made to the Climate Act 2015, having been “drafted in response to the recommendations of the Supreme Court”, according to the responsible Minister. Further, Germany’s highest court and the High Court of England and Wales have cited with approval our Supreme Court’s reasoning in Climate Case Ireland in important climate cases that were won by applicants in those jurisdictions. Litigation before the Irish courts can have important international ripple-effects.

The urge to speed up development and restrict participation – to “get Ireland moving”, as Collison puts it – is not new. Some readers will recall Bertie Ahern, on a visit to China in 2005, declaring “Naturally enough, I would like to have the power of the mayor [of Shanghai] that when he decides he wants to do a highway and, if wants to bypass an area, he just goes straight up and over.”

Collison cites “Haughey’s heyday” as a time when we had “a system that was capable of doing new things quickly.” He blames the “generation of leaders in the 1980s and 1990s” for scandals that damaged the public’s trust in politicians, leading to a transfer of power to agencies. He could have looked further back. Until 1977, planning appeals were made directly to the Minister. However, following some particularly egregious ministerial decisions, this power was removed and placed in the hands of a new, independent decision-maker, An Bord Pleanála.

Collison says “NIMBYs” (the pejorative, again) “deserve our scorn”. I’d remind him that the Aarhus Convention requires the State to protect those exercising their rights of public participation from being penalized, persecuted or harassed in any way for their involvement. On the one hand, those who live close to a project and object often stand accused of being NIMBYs, while those who don’t live nearby are told it’s none of their business and they shouldn’t have the right to object. In any event, instruments of international, EU and Irish law determine who is entitled to participate and who is entitled to bring a challenge.

Collison is therefore simply wrong to write that “Uniquely in developed countries, our system makes it easy for [NIMBYs] by giving anyone legal standing to object to development.” Our system is unusual in providing broad third party rights of administrative appeal in planning matters before ACP. The question of legal standing to bring an action for judicial review is separate to this, however, and is governed by international and EU law. Other developed country parties to the Aarhus Convention and the 26 other EU Member States therefore operate under the same framework for legal standing as we do in Ireland, and it does not give “anyone” (i.e. everyone) legal standing.

While “NIMBYs” and judicial review may currently be under the lens when it comes to the housing and infrastructure crisis, evidence suggests other factors are at work. One might cite, for example, institutional failures in ABP in recent years, leading to a shortage of board members and a large backlog of cases that persisted into the current year (now “mostly cleared”, according to ACP’s chair). One might also cite Ireland’s general shortage of planners, which is well documented. As Andrew Griffin commented earlier this year, “Many councils are unable to fill key posts in forward planning and development management, often losing staff to the private sector or to jurisdictions abroad that offer better pay and working conditions.”

In the field of judicial review, a conundrum arises: which are the good, acceptable judicial reviews and which are the bad ones? Are they ok when developers take them but not individuals or NGOs? Are they ok when airlines challenge passenger caps but not when NGOs challenge new runways? Who is pursuing the “common good” in such cases – the airlines or the NGOs? More generally, are judicial reviews ok when applicants win (thus vindicating the laws passed by the Oireachtas) but not when applicants lose? Or are they all to be discouraged, regardless of outcome (which seems likely to be the effect of prospective changes to be introduced under the Planning Act, though not for litigants with deep pockets)?

In response to the argument that the courts should not ultimately be where planning applications are determined, the chair of the Bar Council, Sean Guerin SC, commented recently that:

“Judicial review is ‘not about the courts substituting their opinion on planning matters for decisions by planning authorities’ […] It is about ensuring that decisions by State agencies which have consequences for the lives of individual citizens are ‘lawfully and rationally’ made in accordance with law.

It is ‘incumbent’ on those responsible for administrative decision-making to have systems and mechanisms that ensure their decision-making meets that ‘relatively low’ bar, he said. Better-quality decision making would mean fewer judicial reviews, he said.”

In other words, the roles of planning authorities and the courts are distinct and different. Planning authorities – the local authorities and ACP – have to decide planning cases on the merits. “Does the proposed project represent ‘proper planning and sustainable development’?” is the ultimate question on the merits under the Planning Act. In an action for judicial review, the courts are not being asked to substitute their opinion on this question for that of the planning authorities. Rather, the question before the courts is: was this planning decision lawful? Has the decision-maker broken the law?

We all have an interest in ensuring that public authorities at least take lawful decisions, of course, not least the Oireachtas as legislator. Given the complexity of planning and environmental law, however, ensuring that public bodies at all levels of the planning system have the required resources and access to expertise to reach legally robust decisions in a timely manner would therefore seem a key area of focus.

It is worth recalling the words of the UK Supreme Court in its famous exposition on the rule of law and access to the courts:

“67. It may be helpful to begin by explaining briefly the importance of the rule of law, and the role of access to the courts in maintaining the rule of law. It may also be helpful to explain why the idea that bringing a claim before a court or a tribunal is a purely private activity, and the related idea that such claims provide no broader social benefit, are demonstrably untenable.

68. At the heart of the concept of the rule of law is the idea that society is governed by law. Parliament exists primarily in order to make laws for society in this country. Democratic procedures exist primarily in order to ensure that the Parliament which makes those laws includes Members of Parliament who are chosen by the people of this country and are accountable to them. Courts exist in order to ensure that the laws made by Parliament, and the common law created by the courts themselves, are applied and enforced. That role includes ensuring that the executive branch of government carries out its functions in accordance with the law. In order for the courts to perform that role, people must in principle have unimpeded access to them. Without such access, laws are liable to become a dead letter, the work done by Parliament may be rendered nugatory, and the democratic election of Members of Parliament may become a meaningless charade. That is why the courts do not merely provide a public service like any other.

69. Access to the courts is not, therefore, of value only to the particular individuals involved. That is most obviously true of cases which establish principles of general importance. When, for example, Mrs Donoghue won her appeal to the House of Lords (Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562), the decision established that producers of consumer goods are under a duty to take care for the health and safety of the consumers of those goods: one of the most important developments in the law of this country in the 20th century. To say that it was of no value to anyone other than Mrs Donoghue and the lawyers and judges involved in the case would be absurd. The same is true of cases before ETs [Employment Tribunals]. For example, the case of Dumfries and Galloway Council v North [2013] UKSC 45; [2013] ICR 993, concerned with the comparability for equal pay purposes of classroom assistants and nursery nurses with male manual workers such as road workers and refuse collectors, had implications well beyond the particular claimants and the respondent local authority. The case also illustrates the fact that it is not always desirable that claims should be settled: it resolved a point of genuine uncertainty as to the interpretation of the legislation governing equal pay, which was of general importance, and on which an authoritative ruling was required.

70. Every day in the courts and tribunals of this country, the names of people who brought cases in the past live on as shorthand for the legal rules and principles which their cases established. Their cases form the basis of the advice given to those whose cases are now before the courts, or who need to be advised as to the basis on which their claim might fairly be settled, or who need to be advised that their case is hopeless. The written case lodged on behalf of the Lord Chancellor in this appeal itself cites over 60 cases, each of which bears the name of the individual involved, and each of which is relied on as establishing a legal proposition. The Lord Chancellor’s own use of these materials refutes the idea that taxpayers derive no benefit from the cases brought by other people.

71. But the value to society of the right of access to the courts is not confined to cases in which the courts decide questions of general importance. People and businesses need to know, on the one hand, that they will be able to enforce their rights if they have to do so, and, on the other hand, that if they fail to meet their obligations, there is likely to be a remedy against them. It is that knowledge which underpins everyday economic and social relations. That is so, notwithstanding that judicial enforcement of the law is not usually necessary, and notwithstanding that the resolution of disputes by other methods is often desirable.”

Years ago, John Temple Lang – a founding father of environmental law in Ireland – agreed to give a keynote speech for me to a group of international PhD students at UCD. John reminded us that day that we should never take democracy or the rule of law for granted – they must be nurtured and defended by each generation anew, he said. Amidst ever-deepening environmental crises, it is crucial that we do not lose sight of the vital roles played by environmental democracy and the rule of law now.

Leave a comment